King James took up the suggestion of John Reynolds made at the Hampton Court conference that a new translation was needed and set in operation the machinery to produce one that the whole church might be “bound to it and none other.” The 54 persons (extant lists have only 47 names) were divided into six companies with two meeting at each Cambridge, Oxford, and Westminster. Fourteen rules of procedure authorized only a minimal revision of the Bishops’ Bible with the translations of Tyndale, Coverdale, Matthew, Whitchurch, and Geneva followed where they were preferable. The old ecclesiastical words were to be retained. If the repeated screenings suggested in the rules were actually done, a careful revision would have been made. A group of overseers composed of two members of each company was to put the whole together.

Information about the actual procedure followed is sparse. Replacements were made in the groups when deaths occurred. Financing plagued the project. Unable to finance the revision himself, King James attempted to raise money from the Bishops, Deans, and Chapters. Church positions were to be held open for the participants, and the universities were to furnish room and board for those working on their campuses. Eventually, the Stationers’ Company supplied 30 shillings a week each for the group that went to London for the final work.

Scattered evidence suggests that the groups were working after 1604. Miles Smith wrote the “Translators to the Readers” which regrettably no longer is printed in King James Bibles but which gives great insight into the purpose of the translation. They aimed to make a good translation better “or out of many good ones, one principal good one, not justly to be excepted against.” A flattering dedication by Bishop Barlow to King James is still printed. Bishop Bilson is credited with chapter summaries called “arguments.”

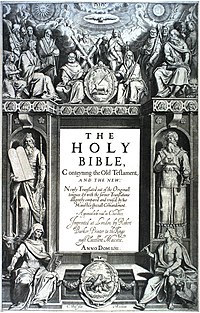

The King James (Herbert 1968: no. 309) was issued in folio and in black-letter in 1611 by printer Robert Barker. It contained the OT, the Apocrypha, and the NT as all its predecessors in English had done. Though free of notes, some variant readings and some alternate translations were indicated, and there were center references. Initial letters decorated books, and curiously enough that to the gospel of Matthew is of Neptune taming the sea horses. The title page carried the phrase “Appointed to be read in Churches.”

The last reprint of the Bishops’ Bible had been nine years earlier. The Geneva was cited in the preface of the KJV, and older translators like Andrewes and bishops like Laud continued to use the Geneva. Though there is no record of an official authorization, the KJV from the beginning dominated the field. There were seventeen editions of the KJV in the first three years, and in the period 1611 to 1640, there were only fifteen editions of the Geneva against 182 for the KJV (Kenyon 1958: 305). Ecclesiastical recognition came in 1662 when the fifth Prayer Book used citations for the Gospel and Epistles from the KJV instead of from the Great Bible.

The KJV has never been free of criticism and has been progressively revised across its history, beginning as early as 1616. Its literary excellencies have always been recognized. For the next centuries it was the Bible of the English reading public.